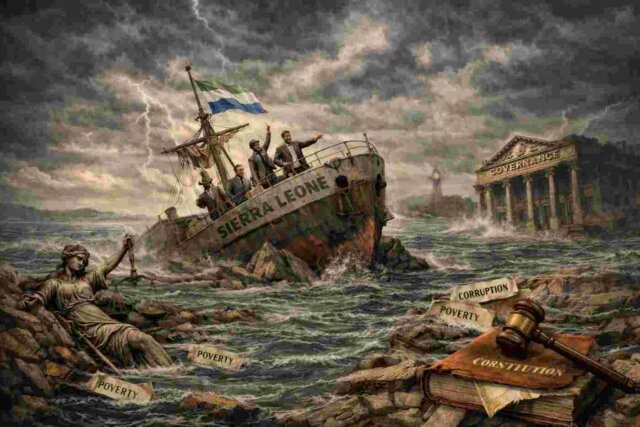

On the streets of Freetown, politics is rarely discussed as an art of judgement. It is spoken of as salvation. Each electoral cycle arrives clothed in promises of final solutions to poverty, poor education, poor health care, corruption, unemployment, and injustice. Each administration presents itself not merely as a steward of the state, but as a corrective force destined to redeem the nation from its past. Yet more than three decades after the restoration of constitutional rule, Sierra Leone remains trapped in a familiar rhythm of expectation, disappointment, and institutional strain. The ship sails, but always under the illusion that a final harbour lies just beyond the horizon.

Michael Oakeshott warned against this temptation. Politics, he argued, is not a voyage towards salvation, but an unending effort to remain afloat in uncertain waters. Shirley Letwin, in her seminal work The Pursuit of Certainty, traced how modern politics abandoned this modest understanding and instead sought redemption through ideology, science, or moral absolutism. Her analysis speaks with unsettling clarity to Sierra Leone’s political condition.

The 1991 Constitution of Sierra Leone is, at its core, a document of moderation. It proceeds from an assumption of human fallibility and institutional limitation. Power is deliberately dispersed among the executive, legislature, and judiciary. The Fundamental Principles of State Policy emphasise accountability, transparency, democracy, and social justice, while recognising that these ideals are to be progressively realised through lawful governance rather than imposed through political will alone. The Constitution does not promise perfection. It promises process.

This constitutional temperament situates Sierra Leone firmly within the Commonwealth tradition of restrained constitutionalism. Across the Commonwealth, courts have consistently rejected political absolutism and affirmed that constitutional authority exists to be exercised prudently, not heroically. In Attorney General v Ibrahim Bangura, the Supreme Court of Sierra Leone echoed this tradition, holding that necessity cannot justify the erosion of constitutional limits. The judgement places Sierra Leone within a wider jurisprudence that treats restraint as a constitutional virtue rather than a political weakness.

Comparable principles emerge from British constitutional law. In Council of Civil Service Unions v Minister for the Civil Service, the House of Lords affirmed that executive discretion, even in matters touching national security, remains subject to legal standards and judicial review. The Commonwealth constitutional order thus resists both sacralised politics and technocratic absolutism, insisting instead on judgement exercised within the discipline of law.

Political practice in Sierra Leone, however, has often strained against this inherited discipline. Rather than accepting politics as a continuous exercise in judgement, compromise, and restraint, political culture has gravitated towards certainty. Governance is framed as a moral enterprise in which leaders claim privileged insight into national destiny, while dissent is cast as obstruction or disloyalty.

The civil war remains the most tragic consequence of this failure. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission identified decades of exclusionary governance, abuse of power, excessive centralisation, and erosion of the rule of law as the structural causes of conflict. Its recommendations closely mirror post conflict constitutional settlements observed across the Commonwealth, particularly the emphasis on institutional checks, decentralisation, and judicial independence as safeguards against renewed instability.

Judicial reinforcement of these principles is evident not only in Sierra Leone but across West Africa. In Charles Margai v Attorney General, the Supreme Court reaffirmed the supremacy of the Constitution over executive expediency. Similarly, in New Patriotic Party v Attorney General, the Supreme Court of Ghana held that constitutional provisions must be interpreted purposively to restrain governmental overreach and preserve democratic balance. These decisions reflect a shared regional commitment to moderation over political certainty.

Public financial governance further illustrates this pattern. Despite statutory frameworks governing public finance, successive audit reports continue to document persistent breaches of fiscal discipline and accountability. Courts elsewhere in the region have addressed similar concerns. In Attorney General of Abia State v Attorney General of the Federation, the Supreme Court of Nigeria affirmed that fiscal power must be exercised within constitutional boundaries and that public finance constitutes a matter of constitutional trust, not executive discretion.

The Sierra Leonean judiciary has articulated the same principle. In Attorney General v Victor Foh and Others, the Supreme Court affirmed that public office is a public trust and that accountability is inseparable from constitutional governance. This reasoning aligns with the Indian Supreme Court’s landmark ruling in Kesavananda Bharati v State of Kerala, which established that constitutional structures limiting power form part of the basic framework of the state and cannot be overridden by political will. Though geographically distant, the jurisprudential logic is shared across the Commonwealth.

International governance assessments reinforce this convergence. The Ibrahim Index of African Governance, Transparency International, and the World Justice Project consistently identify accountability and the rule of law as Sierra Leone’s most persistent vulnerabilities. These empirical assessments echo the concerns expressed in judicial decisions and post conflict governance reforms.

Electoral law provides further illustration. In All Peoples Congress v National Electoral Commission, the Supreme Court of Sierra Leone emphasised that democratic legitimacy depends on adherence to constitutional procedure rather than political outcomes. A similar principle was affirmed by the Nigerian Supreme Court in Atiku Abubakar v Independent National Electoral Commission, which held that elections derive legitimacy from constitutional compliance, not popular enthusiasm alone.

Letwin’s distinction between Hume and Burke thus acquires regional significance. West African political rhetoric frequently sacralises leadership while simultaneously invoking technocratic necessity. Courts across the region have responded by reasserting constitutional restraint as the antidote to political excess. This judicial pattern reflects a deeply Humean instinct embedded within Commonwealth constitutionalism.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission warned that peace depends not on heroic leadership, but on predictable institutions, restrained authority, and respect for law. Letwin’s final warning is that the pursuit of certainty leads to the end of politics itself. When society is treated as an organism with a single good, disagreement becomes illegitimate and governance collapses into managerial control.

Sierra Leone has approached this precipice before and paid dearly for it. Its constitutional text, judicial decisions, reconciliation process, and comparative regional experience all converge on the same lesson. Politics is not a science. It is not a sacred mission. It is an art.

A Humean politics for Sierra Leone would not promise salvation. It would promise restraint. It would respect constitutional limits, tolerate disagreement, strengthen oversight institutions without weaponising them, and accept that governance is an ongoing task rather than a final solution. Such a politics may lack the drama of grand visions, but it offers something far more durable. Stability without illusion.

In a nation still navigating the long aftermath of conflict and mistrust, the greatest danger is not uncertainty, but the false comfort of certainty itself. Sierra Leone does not need another redeemer. It needs steadier hands at the helm, aware that the sea has no final harbour, and that the true task of politics is simply, and humbly, to remain afloat.

SOURCES AND FURTHER READING

Constitution of Sierra Leone 1991, Chapter II

http//: www.sierra-leone.org/Laws/constitution1991.pdf

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Sierra Leone, Final Report

http//: www.sierra-leone.org/TRCDocuments.html

Audit Service Sierra Leone, Annual Audit Reports

http//: www.auditservice.gov.sl

Ibrahim Index of African Governance

http//: www.moibrahimfoundation.org

Transparency International, Corruption Perceptions Index

http//: www.transparency.org

World Justice Project, Rule of Law Index

http//: www.worldjusticeproject.org

Supreme Court of Sierra Leone Law Reports

http//: www.sierra-leone.org/lawreports

Council of Civil Service Unions v Minister for the Civil Service

http//: www.bailii.org

Ghana Legal Information Institute

http//: www.ghalii.org

Nigeria Legal Information Institute

http//: www.nigerialii.org

Indian Kanoon

http//: www.indiankanoon.org