In Sierra Leone, justice has too often existed as a promise recited rather than a service felt. It has lived in constitutional clauses and ceremonial courtrooms, yet remained distant from the everyday struggles of citizens who measure justice not by principle but by access. For those beyond the capital, the law has frequently appeared as a faraway authority, slow to arrive, costly to pursue and indifferent to geography. When distance decides whose voice reaches the bench, the rule of law risks becoming theatre rather than truth.

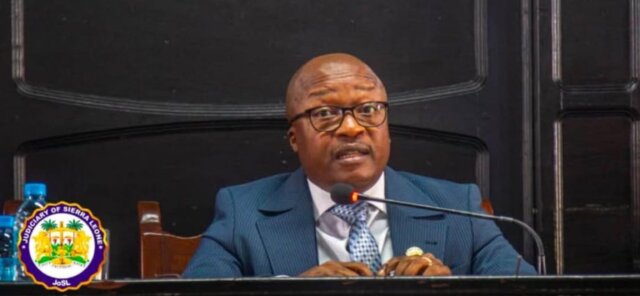

History turns not only on elections or declarations, but on quieter institutional moments when the state recalibrates its relationship with its people. Such moments are rarely dramatic at first glance, yet they carry lasting consequence. The early tenure of Chief Justice Komba Kamanda signals one such inflection point. It confronts a defining question for Sierra Leone’s constitutional order: whether justice will remain centralised and symbolic, or whether it will begin, deliberately and lawfully, to move towards the citizens in whose name it is exercised.

Since assuming office, Chief Justice Kamanda has advanced a reform agenda grounded firmly in constitutional authority rather than administrative habit or personal discretion. Section 120(3) of the 1991 Constitution affirms the independence of the Judiciary, while Section 120(4) assigns to the Chief Justice responsibility for its administration and supervision. By treating these provisions as operational mandates rather than symbolic clauses, the current leadership has sought to convert constitutional principle into institutional practice.

A central pillar of this approach has been the decentralisation of appellate justice. For decades, the Court of Appeal sat almost exclusively in Freetown, imposing severe financial and logistical burdens on litigants from the provinces. The authorisation of provincial sittings in Makeni and Bo marks a structural correction to this inequity. As the Chief Justice has observed, justice delayed by distance is justice denied. By bringing appellate courts closer to citizens, the Judiciary has reaffirmed that justice is a public service owed to the people, not a metropolitan privilege.

This decentralisation initiative also gives concrete expression to Section 137 of the Constitution, which guarantees the right to a fair hearing within a reasonable time by an independent and impartial court. Physical proximity, procedural efficiency and administrative responsiveness are not peripheral to this right but integral to its enjoyment, particularly for rural and economically marginalised communities.

Decentralisation has been matched by renewed emphasis on professional competence and procedural integrity. Under Chief Justice Kamanda’s leadership, magistrates and judges have undergone structured training on the Criminal Procedure Act 2024, a statute designed to strengthen due process, reduce prolonged pre-trial detention and improve efficiency within the criminal justice system. Judicial independence cannot be sustained by institutional autonomy alone. It requires judicial capacity, ethical discipline and technical proficiency. Where competence falters, authority erodes.

These early reforms contrast sharply with baseline conditions documented prior to the current tenure. Civil society assessments, Judiciary reports and development partner reviews consistently identified excessive case backlogs, entrenched centralisation, limited appellate access for rural litigants and insufficient judicial training. The introduction of provincial appellate sittings, revitalised judicial education programmes and strengthened administrative oversight signal a measurable departure from institutional inertia.

At the same time, a measured appraisal is necessary. Judicial reform is not self-executing. Decentralisation without sustained funding risks inconsistency, while training without enforcement risks superficial compliance. Structural challenges such as court infrastructure deficits, legal aid availability and modern case management systems remain unresolved. Recognising these limitations does not diminish the significance of current reforms. Rather, it situates them within the realistic constraints of institutional transformation and underscores the need for collective responsibility across the justice sector.

The reform trajectory under Chief Justice Kamanda also aligns Sierra Leone with comparative regional and Commonwealth practice. In Ghana, judicial decentralisation under the 1992 Constitution expanded regional appellate access and was affirmed by the Supreme Court as a legitimate exercise of administrative authority in the public interest. In Nigeria, appellate circuit reforms have been upheld as lawful responses to backlog and delay under constitutional provisions governing appellate jurisdiction. Kenya’s post-2010 constitutional reforms offer a further comparator, with Article 159 emphasising that judicial authority is derived from the people and must be exercised in a manner that advances substantive justice.

These developments resonate strongly with Sierra Leone’s post-conflict commitments. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission identified a weak, inaccessible and politicised justice system as a contributing factor to the civil conflict. Recommendations 41, 42 and 43 called respectively for strengthened judicial independence, expanded access to justice for rural and marginalised communities, and enhanced professional accountability within the justice system. The current emphasis on decentralisation, ethics and institutional cooperation directly responds to these recommendations, reinforcing continuity between post-conflict commitments and present reform.

At the regional level, the appointment of Chief Justice Kamanda as Chairman of the ECOWAS Judicial Council represents an endorsement of Sierra Leone’s renewed judicial leadership. The Council plays a central role in promoting judicial independence, harmonising legal standards and strengthening cooperation among West African judiciaries. This leadership role further aligns Sierra Leone with the jurisprudence of the ECOWAS Court of Justice, particularly in the protection and enforcement of human rights.

The reform agenda also reflects alignment with international judicial standards. The Bangalore Principles of Judicial Conduct emphasise independence, impartiality, integrity, propriety, equality, competence and diligence. The Commonwealth Latimer House Principles underscore the importance of an independent judiciary operating alongside constructive inter-branch cooperation. At the continental level, Article 7 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights guarantees the right to a fair hearing before competent, independent and impartial courts. By reducing procedural and physical barriers to justice, the current reforms advance Sierra Leone’s obligations under these instruments.

Ultimately, the significance of Chief Justice Kamanda’s early tenure lies not in personal acclaim but in institutional direction. Justice must travel if constitutional democracy is to be meaningful. When courts move closer to citizens, the Constitution moves from abstraction to lived experience. While the durability of these reforms will depend on sustained political restraint, adequate resourcing and continued judicial courage, the direction is clear. Sierra Leone’s Judiciary is moving, deliberately and lawfully, from centralisation towards service, and from public suspicion towards renewed trust.

ENDNOTES

Constitution of Sierra Leone 1991, Sections 120, 124 and 137.

http//:www.humanrightsinitiative.org/publications/ffm/sierra_leone_report.pdf

Reporting on provincial sittings of the Court of Appeal.

http//:www.sarahkallay.com/post/court-of-appeal-to-hold-first-ever-provincial-sittings-in-sierra-leone

Judicial training on the Criminal Procedure Act 2024.

http//:www.ayvnews.com/magistrates-trained-on-new-criminal-procedure-act

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Sierra Leone, Recommendations 41 to 43.

http//:www.sierraleonetrc.org/downloads/Volume1Chapter1.pdf

ECOWAS Judicial Council and regional judicial cooperation.

http//:www.ayvnews.com/sierra-leones-chief-justice-appointed-chairman-of-ecowas-judicial-council

http//:www.wikipedia.org/wiki/ECOWAS_Court